Posted: Thursday, 29 May AD 2008.

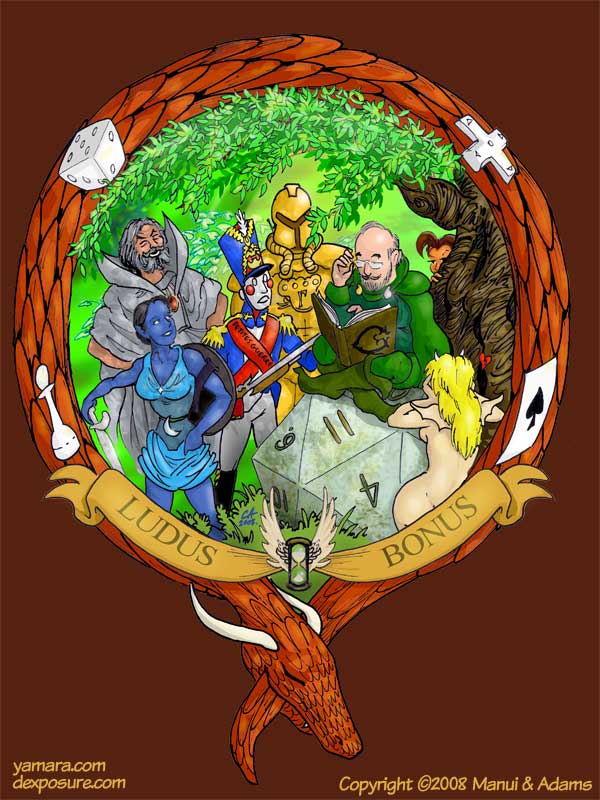

Art for Dexcon 11 (July 16 – 20, 2008).

We had a guest strip at Ben Riley’s Heliothaumic earlier this month, but

between a spike in our ‘real-world’ business and creating the piece above, we didn’t get around to letting anyone know it was running. (Besides, it would get redundant with Ben’s characters frozen on our site, anyway.)

While our comic output has been, to put it generously, unpredictable, Dave Fooden wanted to know back in March if Yamara was going to have a strip memorializing the late Gary Gygax. OOTS, xkcd, Dork Tower, and Penny Arcade all had heartfelt episodes for the man, and while we were not silent, I really couldn’t think of anything much beyond “Good game,” off the top of my head. I repeated it in comments on BoingBoing and DailyKos. It’s what one says when a kick-ass session comes all-too-soon to a conclusion. I trust he’s had even more wonderful times to explore in his new venue.

But memorials used to be things crafted by sculptors rather than us poor cartoon-makers, as the highest form of marking the passage of time that society understood. (Memorials also used to take more time to consider than 24 hours.) So when the Double Exposure crew approached me asking if I was still interested in providing the illustration for this year’s Dexcon, I thought the best way to commemorate our community’s loss was in the way we mark the passage of our community’s time: the convention t-shirt. (The above scene will be available for purchase to all attendees. No idea if con host Vinny Salzillo has plans to sell any online.)

Artists should rarely, if ever, explain their work, but memorials are a case that warrants it: It is a shared art, one where symbol and expression cannot be set too far from the viewer’s grasp, and the artist can claim only so many privileges.

Ludus Bonus is Latin for “good game”. The scene is framed by the ourobouros, in the form of a D&D Red Dragon. This symbol of Eternity coupled with the winged hourglass as the symbol of Time, was common on masoleums and gravestones during the Renaissance and the Enlightenment. The dragon bears elements of four game genres, while a fifth, roleplaying, is celebrated by the scene within.

The foundation of the scene is a reference to the frontispiece of the first edition of the AD&D Player’s Handbook, a circular pen and ink drawing by Trampier of a wizard reading a rulebook atop a huge long-buried six-sided die, beneath the spreading eaves of a tree. The twenty-sider is one Gygax’s gifts to the world, so it rests in place of the ancient d6, as Gygax himself is placed in central honor, able to read from the rulebook of his life at last. And as the angle of the reference piece is from below, so the angle here is from above.

And the wizard is no longer alone, having peopled the land.

The laughing wizard on the left is a homage to Gygax’s own player characters, as he is reminiscent of Caldwell‘s imagining of Mordenkainen from the cover of WG5: Mordenkanen’s Fantastic Adventure. Mordenkainen was a great central leader of Greyhawk, usually preferring others to effect his work, and like the game referee Gygax himself was, he strived for balance and neutrality in all decisions.

The Napoleonic toy soldier represents the roots of Gygax’s creativity in the wargames he played in his youth. “Petites Guerrez” on his uniform refers to Little Wars, the first wargaming rules, devised by H.G. Wells in 1913 in the hopes that by adopting pretend fighting, mankind might learn to avoid actual bloodshed. While Wells devised game rules for toy soldiers, Gygax achieved a greater leap in co-creating roleplaying, essentially making a rules set for “Cops and Robbers”. Gygax also penned an introduction to a new edition of Little Wars before his death.

The shiny futurist figure is someone in powered battle armor from The Legion of Gold, a Gamma World scenario Gygax contributed to. In part, he’s a soldier of the future to contrast with the soldier of the past, but in general he represents things left unsaid: an uncertain identity of an uncertain destiny. The figure is the most passive, but is the most portentous, as the future ever is. Where new discoveries are in our midst, they will have to come from within.

Behind the man himself peeks a certain person who would have never have existed without him.

Before the 1970s, “fantasy roleplaying” referred in the popular mind to a form of adult sexual play, now, amazingly, the minority definition. The succubus groupie is meant as a take on the clothesless Sutherland illustration from the original Monster Manual, now heartbroken and with her wings clipped, for like any groupie, she could never really imprison the spirit of the target of her affection. With Gygax’s passing, he’s escaped from whatever narrowminded “Dark Dungeons” claims were levied against his liberation of the imagination—for as Tolkien emphasized, it is the escape from prison, not from responsibilties—and into the Happy Hunting Grounds of eternal creation, re-creation, and sub-creation.

There is also a personal note to the poor little demoness. In the 1970s, when Gygax’s original blue-covered single-volume Dungeons & Dragons was published, high school pal Mark Rose and I wrote a cover-to cover send-up titled Caverns & Chameleons. In it there is a 4th Level gonzo wizard spell called “Succubi Love”:

With this spell, Gonzo Wizard is allowed to choose one of many succubi as his personal mate. This usually causes wizard to become despondent when without his mate, for his friends will taunt him with such barbs as, “Ha! You!” and other such demeaning insults.

“Ha! You!”—one of Mark’s jokes—has been a staple phrase around our house, with the various romantic foibles Barbara and I have found ourselves in, for the past couple decades. But the absence of Gygax himself makes us consider a very nonromantic “Ha, us.”

My concerns for some things I discovered in Gygax’s work have been ameliorated over the years, if only because a Dungeon Master, even the greatest of them all, cannot control everything a player character is and does. Whatever Gygax may have intended for his evil drow matriarchs, players, artists, and rival game companies have gone and done anything they like with their dark elves. The deep blue elfin creature is the only figure facing away from him; she can stand under the sun, wear the sign of the moon, or indeed, do anything she likes. She makes her own way, for at the deepest core of what Gary accomplished in his time was the strongest reminder that true character relies on our exercising our freedom, our liberty and our life’s joyful pursuit.

—Chris Adams.

New York City,

May, 2008.